The Untroubled Mind • Curator's Essay

The name of this exhibition, The Untroubled Mind, comes from the title given to a series of transcribed comments made by Agnes Martin in 1972. In her statement, Martin refers to what she calls “the untroubled mind,” the state of mind when inspiration is most possible. “The untroubled mind” can also refer to how a viewer may feel after taking in artworks such as those in this exhibition; works which are calm and calming, quiet and quieting, contemplative and capable of encouraging contemplation. The phrase equally applies to artist and audience because of the nature of the transaction that may occur with art: good art is often good because the artist captures – through his or her working process – an essence of feeling in visual form; if the feeling is that of an untroubled mind, then that is what is available to all.

By no means are the artists in The Untroubled Mind all cut out of the same mold: Bernhard Hildebrandt, Christina Manucy, and Denise Tassin may make loosely organic, seemingly improvisational works, but their intentions – and their end results – vary significantly; Claudia McDonough and Jo Smail both work within a grid format, yet they too differ in their purposes; Diane Kuthy and Kris Vandevander both use the motif of repeated small circles, but in different ways. Despite the artists’ diverse range, however, important overlaps exist – many of which can be uncovered through examining the connective tissue linking their works with that of Agnes Martin.

Agnes Martin, who first came to fame in the 1960’s, is often thought of as a Minimalist painter. While her art has always been spare, it is easy to argue she has more in common with Abstract Expressionists such as Ad Reinhardt, Mark Rothko, or Barnett Newman that with the likes of Carl Andre, Donald Judd, or Robert Ryman, all of whom rely heavily on the objecthood of the material they work with; Agnes Martin, more than presenting materiality, paints worlds; her vision is of an austere yet resonant spiritual realm where perfection is, if not attainable, at least approachable.

The notion of perfection is central to the art of Agnes Martin. Barbara Haskell, in an essay accompanying the catalogue for Agnes Martin’s 1992 retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art, writes: “For Agnes Martin, perfection is neither otherworldly – something separate from and transcending the temporal process – nor is it a holiness that inhabits physical matter. It is the intensity of absolute beauty and happiness experienced when our minds are empty of ego and the distractions of the everyday world. In these flashes, worries dissolve and we feel enormous exultation and peace, not unlike the state of grace in Christian theology. However elusive and fleeting these experiences are, they are nevertheless available at every moment to everyone. The task, as Martin defines it, is to further our potential to see perfection within life.”

For viewers unfamiliar with the pared-down visual language that Martin uses, it may seem difficult to fathom how her art addresses the themes outlined by Barbara Haskell; how can simple black lines or dashes of white paint on a blue field be about the seeking of perfection within life? For me, the answer lies in the tension between Martin’s form – orderly, repetitive, rhythmic patterns – and the nuanced touch of her execution: subtle vibrations, for example, in the white dashes in Martin’s untitled (blue watercolor) express the concentrated effort on each mark; the grid is perfectly ordered, and perfection is intensely sought, but the ever-so-slightly quivering human touch from Martin’s hand tells the tale in the most understated way of our own inability to capture the beauty of the world for long.

At the same time, much beauty is realized in Martin’s work; her penetrating relationship with essential elements found in nature are present in the airiness of her blue, the undulation of her lines, the expansiveness of her space. Rather than being pictures of nature (such as a more traditional landscape might be), Martin’s art if from nature, expressing a human response to the perfection and beauty we find in it. “Although I do not represent perfection very well in my work,” comments Martin, “all seeing the work, being familiar with the subject, are easily reminded of it.”

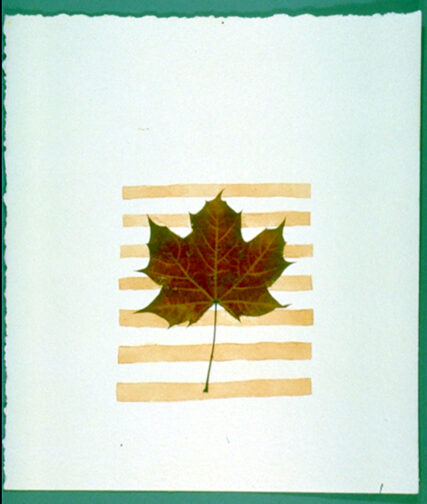

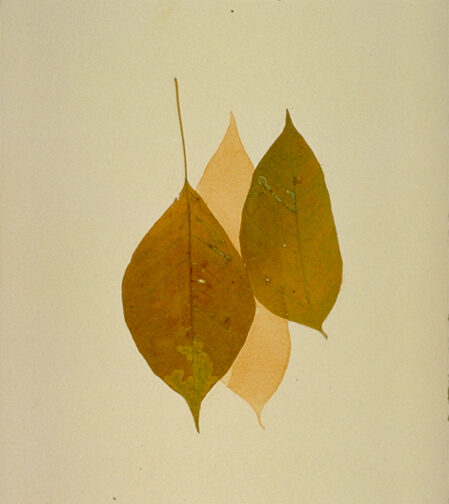

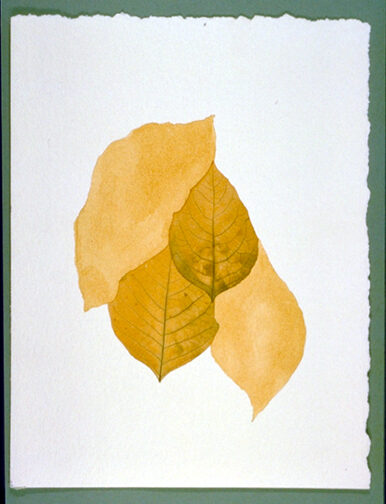

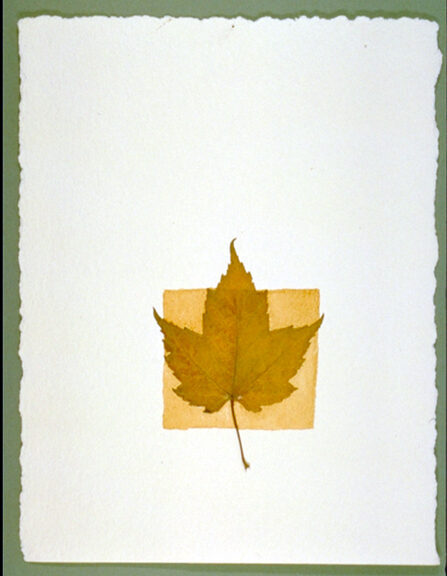

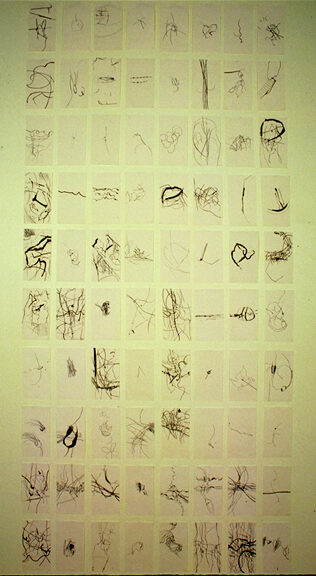

The seven Baltimore artists in The Untroubled Mind share with Martin the outlook that painting is a spiritual endeavor wholly connected to nature and life experience. Denise Tassin’s drawings of delicate lines dancing with leaves perfectly illustrate this point: “I collect fragments of nature,” says Tassin. “I collect these pieces and wholes in an effort to understand myself as a part of ‘it all.’” Other artists in the show may rely upon nature less explicitly, but to no less extent. Kris Vandevander sees his work relating to the microscopic world or (on the other end of the scale) to astronomical phenomena. Diane Kuthy, Claudia McDonough, and Jo Smail all state nature has everything to do with their work. Christina Manucy call her work, “an overall response that I get from being alone in an environment,” and Bernhard Hildebrandt goes so far as to borrow a phrase from Jackson Pollack by commenting, “I am nature.”

As with Martin, the artists do not illustrate natural phenomena, but instead give visible form to feelings inspired by the world around them. Diane Kuthy tells of a time in her life when she used to work in a jazz club hearing live music several nights a week: “I could hear the color, tonality, and timbre in many different instruments and combinations of instruments – it was very emotional for me. I could see visual colors had the same relational possibilities; my paintings became much more expressive.” Jo Smail sees herself as a realist “interested in real experience and real feelings but not necessarily in the identity of things.” Her art has everything to do with human relationships: “I study the gesture of one shape towards another or its passive isolation. They might have edges so soft they melt into each other. It’s become the way I see intimacy; the spaces between us when we care about each other.”

The art exhibited in The Untroubled Mind is marked by a faith in the spare language abstraction. Without explicitly recognizable subject matter, the work leaves meaning largely up to the audience; it becomes, as Manucy says, “more about the viewer,” or, according to McDonough, “vessels for other experiences.” Such a condition aptly describes McDonough’s Untitled, which is literally based upon pieces of pink and yellow candy, though one would never know this in looking at the final painting; the candy is no longer identifiable as itself but rather takes on an air of mystery – the repeated motif exists as openings, or light sources, or ambiguous forms moving through space: the precise meaning is generated individually for each viewer as he or she experiences the painting.

The element of mystery is a central component to the art in the exhibition – the mystery which accompanies the attempt to name something unnamable; to fix in place something unfixable. “abstraction allows you to view through your mind what you cannot see with your eyes,” says Manucy. Smail’s art – barely perceptible in its pale shades of pink and slight variations in tone – perfectly expresses the subtle territory in which these artists operate: what they paint is almost not present – it is ephemeral and light; slow and still. “If I could, I would paint the invisible,” comments Smail. “It is all about nuance and feeling rather than facts.”

The artists are aware of the danger of making abstract paintings. There is always the fear that what they are making is the equivalent of Rorschach tests, arbitrary ink blots upon any meaning can be imposed. Bernhard Hildebrandt echoes a common sentiment when he says, “In many cases there is no difference between abstract painting and wallpaper.” For Hildebrandt, making art entails risk, trust and faith: the risk of failing to make compelling art, the trust that what he deems successful actually has meaning, and faith that he expresses himself “physically as fast as my mind flows.”

Regardless of what each viewer may think of the paintings in the exhibition, the dedicated integrity of the artists is beyond reproach. The creative process for most is a matter of constant reworking and re-evaluation, even as the act of painting can be a flurry of spontaneous activity. After a working session, Manucy always comes “back to the work in a more critical and logical state of mind to determine if the result was inspired or just emotional purging.” McDonough comments, “Paint remover and sandpaper are particular friends of mine. I very often feel as though the touch is not speaking the way I want it to, so I obliterate the painting; then I can start over with a more focused touch.”

Kuthy uses the history of each painting as part of her content – the paint drips, chips and scrapes of a reworked surface hold “metaphoric possibilities” for her. Seeking out small variations on the surface terrain, she often will layer her paintings with stain: “Sometimes these layers seem like window blinds, patterned gates, or transparent fences. I am interested in how each layer is revealed by something that partially conceals it; from the stillness of the outer layer one can discover the turbulence underneath.”

Vandevander is also involved in an intricate layering process. His approach – not unlike Martin’s – is slow and deliberate, involving dipping nail heads in enamel paint in an almost ritualistic fashion. “Usually my process is the same,” he notes. “I sit cross-legged on the floor repeating the same mark over and over. While this in many ways imitates meditation, I do not have the intention of meditating while I paint, or paint as meditation. However, there is a certain amount of focus and discipline in the process of my paintings.”

The “focus and discipline” mentioned by Vandevander is perhaps what is meant by an “untroubled mind.” Not all artists, however, agree as to the meaning of this phrase in relation to their art. Hildebrandt, whose body of work beyond the encaustic in the exhibition tends towards a more restless expressiveness, observes, “Having an untroubled mind can be perceived as possessing a protective cocoon of unconcern.” At the same time, however, he strives for peace of mind and contentment, though “as a rule it is elusive.”

Trying to attain this elusive quality is exactly what makes Martin’s paintings – and the others in the exhibition – so compelling. There is a continual struggle with what Martin calls the world of the “outer mind” – the world of thinking where ego, pride, and separation dominate. Comments from the artists consistently reveal their struggle with achieving a place of calm: “I experience art as an untroubled process,” says Tassin, whose work flows directly from the vast collection of natural objects – bones, shells, dried plants – that she keeps with her in the studio. “What I find troublesome is what surrounds that act of making art: a regular job, paying bills, driving in traffic, and so on.”

It is often hard outside the studio to retain the tranquility that comes with painting. “My mind is sometimes extremely free when I’m in the process of painting,” says McDonough. “When I step back or pause long enough to form a thought, I very often become troubled; filled with doubts.” Jo Smail concurs: “My mind is most untroubled when I lose myself in painting; no fears, no thoughts of before or after. Concentrating on the thing at hand no matter how slight or barely visible. Then I leave the studio and doubts begin again.”

To live a life of integrity is to live with doubt; to be completely comfortable – to have a totally untroubled mind – would be having what Hildebrandt describes as “a protective cocoon.” The great accomplishment of the art in this exhibition is that it provides openings to where an untroubled mind not in denial of the weight of the world is possible. It asks us to slow down; to give ourselves a chance to see it, feel it, know it; to discover renewed hope in the world in which we live.

Peter Bruun

Curator