Perpendicular Dialogues • Essay by Jack Livingston

Breaking Down the Stage - The Work of Denise Tassin

by Jack Livingston

"Two things that determine much of what happens in our lives are circumstance and chance. It is no surprise then that they play equally important roles in the art of nonfiction stories about our lives. It is in a sense the chance nature of reality that draws our attention to one thing instead of another, that sets in motion the combination of eye and hand movements which point a camera in this direction and not in that and which compels us through some urgency to follow and preserve what we see."

Robert Gardner — "The Impulse to Preserve" from Beyond Document — Essays on Nonfiction Film

A relentless constant accumulating mass, Denise Tassin's work is equal parts opacity and transparency. It becomes opaque through sheer volume and velocity - every idea rushes down endless streams and tributaries evoking myriad layers of formability and formalism; it is transparent in that it is in the end autobiographical. As in all good autobiography it tells us something about ourselves as well as the artist. Something hidden, something important, often something we hadn't considered before.

Welcome to the Jungle

Tassin has a taste for complexity, even when cloaking it in the often deceptive simple. The complexity is more than the amount of work presented and voluminous intrusion of space she favors. It is the swivel-headed action and reaction, the swelling thought processes, the stripping and regrouping of her incessant grid foundations. Like our human jungle it is filled with incongruities, not opposites. Violence and passivity, glory and absence, purity and muck, candy and bone. It is a sultry overwrought Tennessee Williams's cackle laid over the signature idiosyncratic pianoistics of Glenn Gould. It is the ecosystem of humanity.

Signature Verité — Pulp over Plastic

Fictional documentary is often more accurate and appealing than so-called pure documentary. Like a diary, the 'pure' documentary is in fact deluded by its own perceptions of 'honesty' and 'truth'. Tassin's autobiographic work uses a form of fictional documentary to reach for something beyond fact; it is gutsy faux because it is fictional truth.

In much of her work, Tassin sifts through her world for transfixing objects and materials, particularly the serial and discarded. She seeks out things with a past but not too overt in their drama. These objects and materials are manipulated by the artist directly, through context, or association then re-edited for presentation.

Her work is not collage — she does not combine in the usual sense. She is much more the heir of Joseph Buey's spiritual serializations than of Edward and Nancy Kienholdz's massive odes to the common man.

To date, Tassin has generally chosen to forsake new technologies herself (i.e. electronic technology) in favor of the slosh of fluid upon surface, and the arrangement of object in close proximity to object. She has chosen paper over silicon.

She instead chooses to embrace collaboration with techno enthusiasts.

Sticky Goo Persuasion

The debris of wind-strewn and crawling involuntary nature stuck in cruel beatific chance on her large format outdoor paintings is the most explicit example of her stratagem. What appears at first look to be chance fact is actually controlled fiction. The artist has chosen the marks, the size, the location, and, most telling, the place where the sticky goo traps lay. What is trapped simply serves her purpose. A greater truth develops.

Transformation

Through these acts of serial exploration and mock scientific experimentation Tassin's work achieves a transformation. This isn't an explosive, orgasmic epiphany; there's no dramatic arc. Instead, there's a sustained and prolific moodiness, an externalization of chains of internal thought. Tassin's constant serialization of these chains is so extreme they fuse the viewer with the experience. It's difficult to step back and reflect because there's nowhere to go.

Manipulation

Manipulation is Tassin's forte, her most human aspect. Rendering the ALL through piles and layers of form, modalities, and concept fever. The rapid manipulations, shifting fact to fiction and back again, leaves the viewer dazed. Through this relentless orchestration the artist comes to terms with herself and the events —past and present —which surround her. She plays with chance à la John Cage but like any smart maestro (Cage himself included) she is always seeking a balance between cool control and mind-altering accident, humor and pathos.

Broken Chatter

The choice to be an artist — choosing to work in a visual language rather than a verbal — means something. Words rarely enter the work itself, but Tassin's well-constructed titles reveal a taste for the poetic. In interviews Tassin is always articulate, earnest, funny, and very concise — yet one senses that she's frustrated by her own answers. This makes sense. Like many visual purists Tassin's work is all about getting beyond language. Language is the barrier we seek to break so we can feel.

Linear to Circular and the Great Leap

Tassin works most often on the platform of a grid or frame. The grids can be read as a whole (geometry) or in sequence (cinematic). The work begins in a linear way before veering into a seeming haphazardness, bending toward the circular — endless looping, sequencing blots and bleeps, clipped stories within stories. And always, the circle is broken. At that break, the artist and the viewer hang suspended, mid-leap.

Any topography near Tassin's work becomes yoked there simply because she is a tremendous overt human force, an observable entity with an intentional human face. The autobiographical lamb from which to feast.

Re-modernist

Tassin's work though dense with postmodern reference and materials is in fact more modernist than post. She is an idealist, a re-modernist. For Tassin to take a step back in time is necessary.

Necessary and profound, because it wrenches us into an ocean of possibilities. This work is about fusion not confusion. The veracity of her personal fictions is that idealism pays off. Release — a blood purge with secrets told — feeds the heart of being. The jungle of humanity is a place to occupy not a place to simply observe.

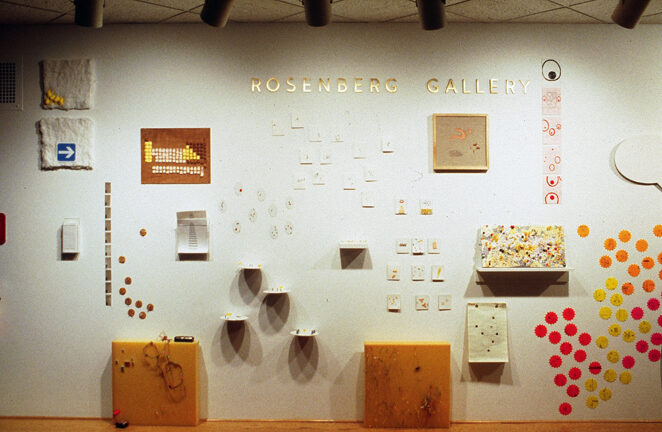

In this world the round bright colored candy wafers the artists adores, the glorious enamel Chesapeake greens of her new colorfield paintings, the blue velvet shelves of pseudo-science display, the myriad psychotropic medications in playful configurations, all the smeared blood and carcass now in retreat, the line and ephemeral ceiling strips, photograms, the Magic Marker attacks and swirl brush hits, are as much a pure thing as the single fallen leaf ghosted on the white white field of gesso divine.

Perpendicular Dialogues • Essay by Laura Burns

Perpendicular Dialogues

Here we are. Let us say Yes to our presence together in Chaos. —John Cage

History

If one catapults oneself into outer space such that one’s vision includes the so-called larger picture, it might be possible to see that most human endeavors are in some form an attempt to make sense of chaos. The project that has evolved as Perpendicular Dialogues did not begin in a void (since that is socially impossible), but did begin as an open-ended meeting of minds with no particular agenda other than to make something happen. The result of this series of conversations between five artists conducted over 17 months is not perhaps a traditional collaboration in which the group moved toward one common goal, so much as a series of individual works that play off of one another and that have been influenced, shaped, and changed by the ideas of the others.

Process

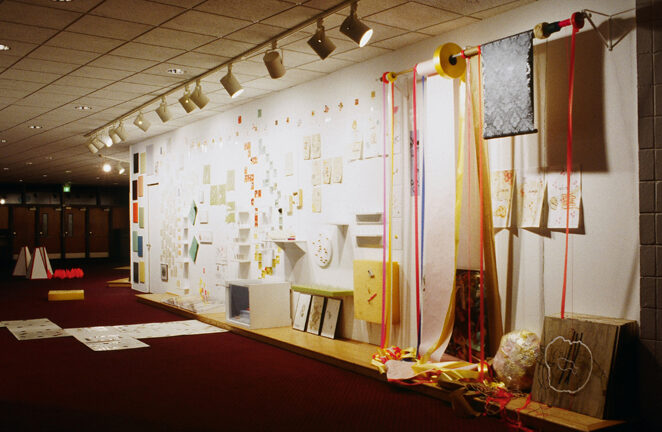

In a conversation about writing, John Cage told Joan Retallack, “You know, you can always begin anywhere.” It would be possible to locate (map) the origins of Perpendicular Dialogues in numerous places, but I will place the center point of my virtual Mercator projection inside Denise Tassin’s head. Rather than censoring her artistic process, Tassin chose to remove boundaries, allowing all ideas and materials to become playgrounds for thought. The result is a map of her imagination and internal thought process. Using objects that range from sequins and Necco wafers to finger condoms, pills, biology, and current events, Tassin has created a topographical history that moves from childhood to the present. Time becomes an object; but her map rather than defining space and boundaries, opens them to the infinite. She has also projected her drawings/musings into the bodies of others. Throughout the year, Tassin and the dancers conducted movement experiments that are incorporated into the visual fabric of the exhibition.

Movement

Woodson imagined a map as a pathway plotted in successional movements through space, causing her to think linearly as opposed to gesturally. The sectional nature of her dancers’ movements occurs as a series of vignettes loosely based on Tassin’s images, while the influence of Tassin’s work spurred her to more completely design the space within which movement takes place. Integrating the shape and lines of the stage and the gallery with the shapes and lines of the dancers, space itself becomes a form of action, while the dancers take on qualities of sculpture and drawing. Through the use of the gallery and via Rueb’s online presentation of the dancer’s daily travels, aspects of performance take place outside the confines and the context of the proscenium, such that audience members must shift their bodies and their attention, creating an expanded spatial, social, and bodily awareness.

Location

Rueb’s Stomping Ground examines where people move, juxtaposing Cartesian space and virtual space and the mapping of choreographed versus everyday movement. Dancers wearing Global Positioning System devices track their daily movements as they go to class, visit friends, and do errands. The maps of their wanderings accumulate on the gallery walls and on line in an indexical diary that reveals habit rather than personal narrative and transfers footsteps taken on solid ground into the space of the virtual. Rueb also maps the gallery space with an implicit grid of horizontal and vertical banks of TV monitors, while 12 small cameras capture the movement occurring within that invisible net(work). Everyone becomes a performer as both the formalized movement of the dancers and the random movement of passersby flicker across the screens, breaking down bodies and creating a new sense of how they move through, fit into and are shaped by space.

Sound

If Rueb looks at the where of movement, Andrew Cole is dealing with how dancers move, creating sound from gesture. Movements are no longer a response to sound; they are one and the same. His is an aural map of the finite space of the individual body. Because this space/body is in constant motion, its musical map continuously changes and recreates itself, and the dancers become generators rather than receptors of music.

Time

In Perpendicular Dialogues, lines between the performative arts and the visual arts are blurred as dance, sound, painting, video and drawing all play with permanence and impermanence. Connections between time and space are revealed through Rueb’s tracking of bodies in front of the camera lens and Tassin’s capturing of insects and forest detritus on her sticky paintings. Each catches movement, but Stomping Ground’s hold on its bodies is fleeting and devoid of physical contact, while Tassin’s paintings pull objects to them and physically detain them. But permanence is relative; insects and leaves will eventually decay in a slow movement of disappearance. Perhaps the difference between technology and biology is just a matter of time.

Laura Burns

Artist and Director of the Rosenberg Gallery, Goucher College